| Location: | Bladder wall |

| Behaviour: | Mostly aggressive |

| Diagnostics: | Blood and urine analysis, histology, imaging of the urinary system |

| Treatment: | Surgery, chemotherapy, anti-inflammatory drugs, local treatment |

| Prognosis: | Guarded |

| Location: | Bladder wall |

| Behaviour: | Mostly aggressive |

| Diagnostics: | Blood and urine analysis, histology, imaging of the urinary system |

| Treatment: | Surgery, chemotherapy, anti-inflammatory drugs, local treatment |

| Prognosis: | Guarded |

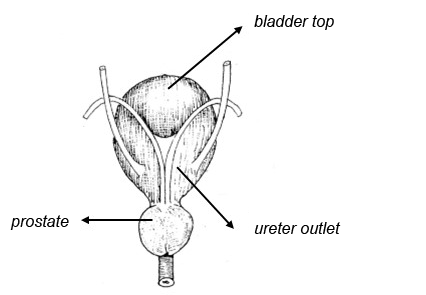

This tumour type is located in the urinary bladder wall, mostly at the ureter outlet and the bladder neck, less often at the bladder top.

Bladder tumours can have multiple causes. Exposure to older generations of garden chemicals/flee products and possibly chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and obesity can have an influence on their development. Newer spot-on flee products are considered to be safer than the powders that are poured onto the fur.

The tumour can form lumps on or thicken the bladder wall which can lead to partial or complete obstruction of the urinary tract. Most bladder tumours are malignant and can spread towards the liver, bones (rare), lungs and lymph nodes.

2% of all tumours in dogs.

There is a higher risk to develop this tumour type among Scottish Terriers, Shetland Sheepdogs, Beagles, West Highland White Terriers and wire-haired Fox Terriers vs other dogs.

The tumour takes up space within the bladder and can invade the bladder wall, which can cause bloody urine, difficulties urinating, frequently urinating in small amounts, sometimes even limping due to metastases towards the bones. The symptoms of a bladder inflammation (difficulties urinating/ frequent and small amounts of urine) can temporarily disappear after administration of antibiotics. If there are repeatedly urinary tract issues, a bladder tumour should be considered as a possible cause.

For dogs where the diagnosis of a transitional cell carcinoma is confirmed, it is advised to stage the cancer through X-rays of the chest, ultrasound of the abdomen and imaging of the urinary tract.

During a rectal examination, the veterinarian can feel a a thickened urethra. Other possible findings include enlarged lymph nodes and a tissue mass in the bladder. A normal rectal examination does not exclude the presence of a transitional cell carcinoma.

Cancer cells can be present in the urine of up to 30% of dogs with a transitional cell carcinoma. This means that if the veterinarian does not encounter cancer cells in the urine, this is no guarantee there’s no tumour present. Moreover, it can be difficult to distinguish these cells from inflammatory cells present during bladder inflammations. Antigens specific for a transitional cell carcinoma can be tested in the urine, but give high false-positive results and thus limit the value of the test.

A positive BRAF mutation testing confirms the presence of transitional cell or prostate carcinoma. If no BRAF mutation is detected in the sample, it may be because (1) there is no cancer present, (2) there is a tumour, but it is not caused by the BRAF gene mutation, (3) the urine sample does not contain mutated cells, even though a carcinoma is present.

Through ultrasound, radiography or a CT-scan of the bladder, the veterinarian can assess the tumour’s location and extensiveness. This information allows the veterinarian to estimate whether surgery’s possible and/or draft a plan to excise the tumour.

Histopathology is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. The veterinarian can obtain a tissue sample by making a surgical incision in the bladder, with an endoscope (a camera with forceps inserted into the bladder that can remove a piece of tissue) or catheterization (a catheter inserted via the urethra into the bladder which removes a tissue sample of the tumour through trauma). There is a preference to obtain the tissue samples via an endoscope as this allows an inspection of the urinary tract and is a non-invasive way to retrieve samples. In case the tissue samples are poorly differentiated, it can be difficult to make a distinction between a transitional cell carcinoma and another tumour type. In that case, a special dye can be used on the sample (immunohistopathology uroplakin III colouring). This dye colours certain cells from the urinary tract that appear in more than 90% of transitional cell carcinomas and is considered as a typical marker for this tumour type.

| Stage tumour | tumour status |

|---|---|

| Tis | well delineated tumour |

| T1 | superficial lumpy tumour |

| T2 | tumour invading the bladder wall |

| T3 | tumour invading the surrounding tissues |

| Stage lymph node | lymph node status |

| N0 | no local lymph nodes involved |

| N1 | local lymph nodes involved |

| N2 | local and nearby lymph nodes involved |

| Stage of metastasis | metastasis status |

| M0 | no proof of metastasis |

| M1 | distant metastasis present |

Surgery can serve 3 purposes

Reducing the size of the tumour mass can theoretically increase the chances of success of other treatments. Complete removal of a transitional cell carcinoma in the bladder is often not possible because they frequently occur at the ureter outlet, or because the urethra is involved and, in some cases, because metastases are present. Surgery is rarely curative but can have an important function for the dog’s quality of life as it can decrease obstruction of the urinary tract, thereby enabling the dog to urinate normally again. Another option is to create a bypass between the bladder and the urethra (because the passage to the urethra is blocked by the tumour). How long the dog survives after placing these bypasses or stents has not been extensively reported and varies between a few days to up to a year. Of note, a bypass means that most times the urinary flow is no longer controlled by a bladder sphincter and the dog becomes incontinent.

Information about the suitability of radiotherapy for transitional cell carcinomas in dogs is limited and should be further examined. A study with 21 dogs treated with radiotherapy described an overall median survival time of 654 days of which dogs were symptom-free during 317 days. Acute side effects were mild and self-limiting (inflammation of the colon (38%), redness or thickening of the skin (19%) and difficulty urinating (5%)). Late complications included narrowing of the urinary tract (5%).

The most common treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder consists of chemotherapy, administration of anti-inflammatory drugs or a combination of both. Although medical therapy is not usually curative, several different drugs lead to disappearance or stabilization of the tumour. It’s also possible that after a while, the cancer cells are no longer sensitive to the antitumoural medication. When this is the case, the treatment must be switched to the next drug. To catch the occurrence of therapy resistance in time, it is important to do a regular follow-up of the dog (every 1 to 2 months). In general, a treatment is maintained as long as the disease is under control, the side effects are acceptable, and the quality of life is ok. Through medication, in 75% of dogs with a transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, the tumour can be kept under control. The quality of life is usually very good. The survival can be up to a year, but varies between dogs. When anti-inflammatory drugs such as piroxicam are administered, one must be aware of the side effects of their long-term use, such as digestive issues (in particular ulcers). In case of vomiting, black diarrhoea and a lack of appetite, the medication must be stopped, and the symptoms treated. After this and if appropriate, the veterinarian can advise to switch to another type of anti-inflammatory drug.

Local treatments consist of inserting chemotherapeutics into the bladder and photodynamic therapy.

Not much has been published about bladder chemotherapy in dogs. In a small study, it seemed to be well tolerated and the tumours did shrink or stopped growing after this treatment. However, serious side effects can occur when the chemo is absorbed from the bladder into the bloodstream. This treatment is therefore only advised when there are no other options left. Furthermore, after this treatment, precautions must be taken concerning the urine collection of the treated dog as the concentration of the chemotherapeutic in the urine after a bladder rinse with this chemotherapeutic is much higher than after the classic intravenous administration.

Photodynamic therapy of the bladder consists of administering a photodynamic agent (a compound that reacts with light) intravenously, after which it selectively accumulates in the tumour. After this, the tumour is illuminated via a light source inserted into the bladder. The illumination causes a chemical process in the cancer cells which have taken up the photodynamic agent after which they eventually die. The illumination can be painful.

In humans with high-grade superficial tumours of the bladder, a weakened bacterium, named bacille Calmette-Guérin, is applied into the bladder. This bacterium stimulates the immune system to recognize the tumour and to attack it. So far, the reports about this approach in veterinary medicine are limited. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is a weakened bacterium that has been used in a similar way in dogs and led to results in some dogs. The treatment is mostly effective when only the superficial layer of the bladder wall is affected. Unfortunately, the tumour has often already penetrated the deeper tissue layers before the dog shows symptoms and is diagnosed. Furthermore, this therapy is not commercially available.

The treatments so far can cause remission or stabilize the tumour during several months whilst maintaining an excellent quality of life. However, most dogs die from the consequences of this tumour. Survival is strongly linked to the tumour stage at the moment of diagnosis.

| Tumour stage | median survival |

|---|---|

| T1 of T2 | 218 days |

| T3 | 118 days |

| N0 | 234 days |

| M0 | 203 days |

| M1 | 105 days |

AURA Veterinary

Surrey, United Kingdom

Hospital for Small Animals, Royal (Dick) Vet School of Veterinary Studies

Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Anicura Clinica veterinaria Malpensa

Samarate, Italy

Auna Especialidades Veterinaria

Paterna, Spain

hello@auravet.com

+44 (0)1483 668100

https://www.auravet.com/clinical-trials/

Veterinary clinic of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

Liège, Belgium

Annick.Hamaide@uliege.be

rbernardes@uliege.be

https://www.cvu.uliege.be/cms/c_9997232/fr/cvu-carcinome-urothelial-du-chien

CHV AniCura Armonia

Vaulx-Milieu, France

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

Merelbeke, Belgium

cardiologie.khd@ugent.be; Gitte.Mampaey@UGent.be

https://www.ugent.be/di/khd/nl/onderzoek/betere-hartscreening-chemo-hond

AURA Veterinary

Surrey, United Kingdom

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

Merelbeke, Belgium

simone.janssen@UGent.be

https://www.ugent.be/di/khd/nl/onderzoek/fluorescence-lifetime-imaging-info-dog-owners

Division of Radiation Oncology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Zurich

Zurich, Switzerland

+41 44 635 81 12

https://www.tierspital.uzh.ch/forschungsprojekte/lattice-oder-sbrt-strahlentherapie-bei-grossen-tumoren/